Why China is Good at Math: The 4,000-Year Culture That Thinks in Numbers

China’s relationship with maths dates back to over 4,000 years ago. If you know China today for strong high math scores and olympiad winning students, you’re actually seeing the latest chapter of a very long story.

What makes mathematics in China unique is not just what they discovered, but how they thought: not with equations and symbols like the West, but with rods, visual tricks, and “recipes” that make math intuitive.

Let’s break it down clearly.

Chinese Math History: Counting rods & math that you can touch

Long before pen-and-paper arithmetic, ancient Chinese mathematics used counting rods, small sticks placed on a flat board. Think of them as the world’s original calculator.

- Each column = ones, tens, hundreds

- Move rods around → you’re watching the math happen

- Rearranging rods = solving equations visually

This tool shaped the entire style of Chinese mathematics:

✔ Numbers were physical things you could move

✔ Hard problems became puzzles

✔ Visual intuition replaced abstract algebra

✔ It led directly to methods like early linear algebra (solving multiple equations at once)

This “move the sticks until the numbers line up” mindset powered real-world problem-solving for more than a millennium.

Mathematics as a set of recipes, not abstract theories

While Greek math built towers of logic (“First we prove A, therefore B…”), Chinese math followed a different philosophy:

Give me a real problem → I’ll show you a step-by-step recipe to solve it.

These recipes appear throughout ancient Chinese texts:

- How to divide land

- How to calculate taxes

- How to measure the height of a tree using shadows

- How to find the area of a field

- How to solve simultaneous equations

- How to keep a calendar accurate for farming

This is why Chinese math feels so modern, China was writing “algorithms” 2,000 years before computers existed. The recipes were like code, making up algorithms, which are the heart of computer science.

The book that taught an empire how to calculate: The Nine Chapters

If ancient China had textbooks in schools, The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art would be the national curriculum.

It includes:

✔ Fractions explained through division

“You divide 17 by 5 → you get 3 plus 2/5. That’s what a fraction is.”

✔ Geometry as practical steps

“Square the diameter → triple it → divide by 4.”

That was their algorithm for the circle area.

✔ Solving systems of equations

Three unknowns? No problem.

Arrange rods in columns and eliminate them visually, basically Gaussian elimination, 1,800 years early.

✔ Square roots & cube roots

Extracted digit by digit, just like modern methods.

✔ Right-triangle problems

Including a Chinese version of Pythagoras’ theorem (Gougu rule).

In short, The Nine Chapters was the world’s most complete practical math handbook for 1,500 years.

Liu Hui: the man who asked “why does this work?”

Most early Chinese math said how to do something, Liu Hui (3rd century) asked:

“Why is this algorithm right?”

In layman terms, he:

- Cut shapes into pieces

- Rearranged them

- Showed visually that two volumes had to be equal

- Proved circle-area formulas

- Approximated π to 3.14159 with a 3,072-sided polygon

- Invented an early version of limits (yes, 1,500 years pre-calculus)

He didn’t use symbolic proofs, he used diagrams, cutting, and comparing pieces. It’s proof you can see, not proof you need a PhD for.

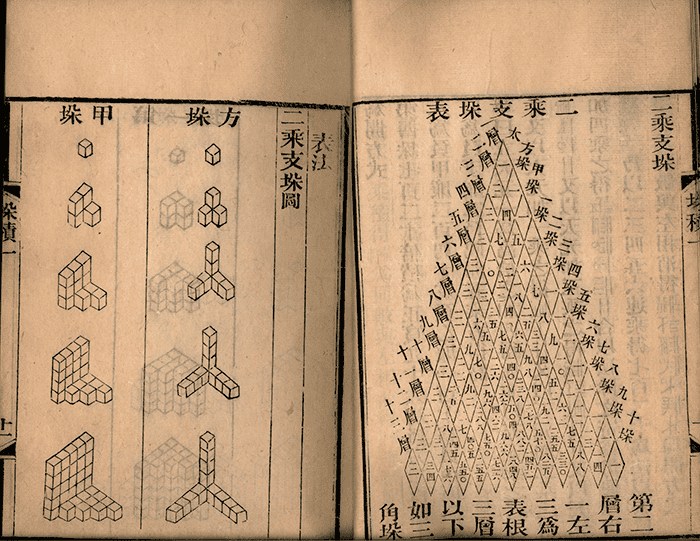

The Golden Age: 11th–13th century algebra that looked shockingly modern

Chinese mathematicians during the Song–Yuan dynasties developed:

✔ The “celestial unknown” system

A way of laying out polynomial equations visually on a board—like a spreadsheet of exponents.

✔ Early Pascal’s Triangle

Yang Hui documented binomial coefficients long before Pascal.

✔ Solving 10th-degree equations

Using refined step-by-step methods similar to Horner’s method.

✔ The Chinese Remainder Theorem

Qin Jiushao came up with it while solving calendar problems, still used in computing and cryptography today.

✔ Multi-variable systems

Zhu Shijie worked with four unknowns using a visual layout that looks like a matrix today. They built an algebra without symbols, using position, rows, columns, and patterns. It’s like inventing Excel centuries early.

Why ancient Chinese math declined (but didn’t die)

From the 14th century onward:

- Counting rods fell out of use → the methods tied to them became harder to teach

- The abacus replaced rod boards → good for arithmetic, bad for algebra

- Symbolic algebra never fully developed (until Western contact)

- Books became too difficult to understand without teachers

- Mathematical traditions became fragmented

But the culture stayed: respect for math, fascination with patterns, and emphasis on learning through methods.

When Western math arrived, China blended it with its own ideas, creating a hybrid tradition that we see today.

So… why are Chinese students good at math?

It’s easy to think Chinese students are “naturally good at math,” but that’s not true! It’s a system and a cultural habit built over thousands of years.

Here’s the deeper breakdown that actually explains it.

1) Early number sense is easier in Chinese

This sounds small, but the impact is huge. Numbers in the Chinese language follow a perfect pattern. Kids can learn the whole number system in minutes:

- 11 = “ten-one”

- 12 = “ten-two”

- 23 = “two-ten-three”

- 58 = “five-ten-eight”

Meanwhile in English:

- “Eleven”, “twelve” = irregular

- “Forty” vs “four” → different sounds

- Teen vs. -ty endings → confusing for children

What’s the difference?

✔ Kids reach “place value understanding” faster

✔ Mental math becomes natural

✔ Fewer exceptions = less cognitive load

This head start doesn’t guarantee success, but it makes math feel more intuitive from age 4–7.

2) Chinese teaching focuses on mastery, not “covering the curriculum”

In many Western systems:

“We taught the topic. Whether they mastered it is another question.”

In China:

“We don’t move on until nearly everyone gets it.”

This leads to:

✔ fewer gaps

✔ more confidence

✔ a strong foundation for harder topics

✔ less “math trauma”

It’s like building a house: China makes sure the foundation is solid before building the roof.

3) Practice cultures aren’t punishment — they’re normalized

Western students often see practice as “being slow” or “not smart enough.” Chinese students see practice as normal, neutral, expected. This starts early:

- calligraphy practice

- music drills

- repetition in language learning

- memorizing poems

- basic math drills

To Chinese parents, teachers, and students, practice is not a sign of failure. It’s just how you improve at anything, same as sports or piano.

This creates a powerful psychology:

✔ students don’t panic when something is hard

✔ they assume effort → improvement

✔ they stay with problems longer

✔ they develop resilience instead of avoidance

4) Teachers are trained to teach math, not just “assigned” to math

In Chinese schools, especially primary schools:

- Many teachers specialize ONLY in mathematics

- They receive deeper training in how to teach concepts

- They use carefully designed teaching routines that build step-by-step logic

- Lessons are rehearsed, polished, and standardized

When the average teacher is mathematically confident, the average student becomes more capable too.

5) The classroom prioritizes reasoning, not “creative guessing”

In many Western classrooms:

“Any strategy is okay as long as you get the answer.”

In China:

“Learn the most efficient method first. Then, once it is automatic, explore alternatives.”

This creates:

✔ faster accuracy

✔ less cognitive chaos

✔ a shared classroom method

✔ fewer misunderstandings

✔ a clear path to success

Chinese lessons often follow the same structure as ancient Chinese math books:

Step-by-step → demonstration → explanation → practice.

6) Homework volume isn’t the magic — the quality of practice is

Western media often imagines “endless homework.” But the core difference is how students practice:

Chinese homework tends to:

- reinforce one concept deeply, not ten shallowly

- use variations of the same idea (polya-style reformulated problems)

- cycle back to older concepts

- train precision AND understanding

- avoid ambiguous tasks that confuse beginners

This turns understanding into automaticity, which frees up brain space for harder reasoning later.

7) Parents expect their kids to succeed in math — not because they’re strict, but because math is seen as learnable

Western media often imagines “endless homework.” But the core difference is how students practice:

Chinese homework tends to:

- reinforce one concept deeply, not ten shallowly

- use variations of the same idea (polya-style reformulated problems)

- cycle back to older concepts

- train precision AND understanding

- avoid ambiguous tasks that confuse beginners

This turns understanding into automaticity, which frees up brain space for harder reasoning later.

8) The education system is designed around math historically

This goes back 2,000 years. Ancient China needed math for:

- building roads

- managing floods

- calculating taxes

- distributing grain

- farming calendars

- military logistics

For centuries, scholars could not pass imperial exams — the gateway to government jobs — without mastering basic math. Math became part of what “an educated person” looks like.

Today, that tradition persists:

- math is core

- math is respected

- math is the gateway to opportunities

- This cultural memory shapes modern attitudes.

What makes Chinese mathematics truly unique? (The short answer)

If you only remember one thing, remember this:

Chinese mathematics is visual, practical, and algorithmic.

It solves real problems using methods you can see, touch, and repeat.

- Greek math = abstract theory

- Chinese math = real-world calculation

- Modern math = a fusion of both

China discovered that you don’t need symbols to do powerful math—you need good methods.

Start Your Journey to Study in China Today

Chinese mathematics is so much more than modern exam scores. It’s a 4,000-year story of humans finding visual and practical ways to understand the world. It teaches us one big lesson:

Math becomes easy when you can see it, move it, and use it.

This same mindset shapes education across China today: learning by doing, understanding through application, and turning knowledge into skills.

Choosing to study in China is a life-changing decision that opens the door to world-class education, cultural diversity, and exciting global opportunities. Whether you’re researching top China universities or preparing your China university application, having a trusted partner can make all the difference.